And this is what I saw…

Woohoo!

To Jacob Gube and Smashing Magazine, thank you so much for including my tutorial in your list!

If you’re curious about the tutorial, just click on this.

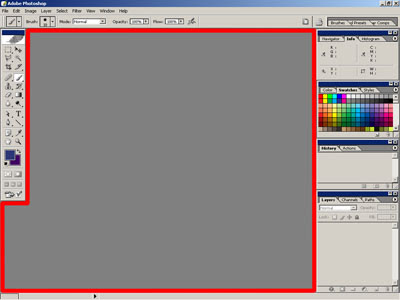

The area/space inside the red outline is the “big gray area” I’m referring to.

The area/space inside the red outline is the “big gray area” I’m referring to.

I don’t find the need to stress this to Mac users because instead of a big gray space, you’ll see your desktop wallpaper instead. Obviously, that means you’ve got nothing to work with.

What you should do upon launching/running Photoshop is to either open an image file or make yourself a canvas.

Opening an Image File

Opening an image file in Photoshop is very much like opening a file in any other program. Click on ‘File’ and then click on ‘Open’.

In the ‘Open’ window/dialog box that appears, find the file that you want opened, click on it, and click on the ‘Open’ button. Now you have a “canvas” to work with/on.

By the way, Photoshop can open a wide range of image file formats as well as a couple of “non-image” file formats. To see all the file formats that Photoshop recognizes/supports, click on the button at the end of the dropdown menu field labeled “Files of type”. For starters, I would advice you to stick with the JPEG (or .jpg) file format for now, unless you already know something about the other image file formats.

A word of caution for those who are about to take or have taken this route. Read this VERY CAREFULLY and UNTERSTAND IT WELL. For those who opened an image file, BE VERY CAREFUL IN SAVING YOUR WORK! If you’ve just put a mustache on someone’s face or whatever it is that you will be doing or have already done, once you save your work and close that image, YOU WILL NEVER EVER BE ABLE TO RESTORE IT BACK TO ITS ORIGINAL STATE! So what I advise you to do is save your work with a different filename. JUST DON’T OVERWRITE THE ORIGINAL.

A word of caution for those who are about to take or have taken this route. Read this VERY CAREFULLY and UNTERSTAND IT WELL. For those who opened an image file, BE VERY CAREFUL IN SAVING YOUR WORK! If you’ve just put a mustache on someone’s face or whatever it is that you will be doing or have already done, once you save your work and close that image, YOU WILL NEVER EVER BE ABLE TO RESTORE IT BACK TO ITS ORIGINAL STATE! So what I advise you to do is save your work with a different filename. JUST DON’T OVERWRITE THE ORIGINAL.

Creating a Canvas

To “create” a blank canvas, click on ‘File’ then ‘New’. A window will appear where you can specify your canvas’s dimensions, resolution, color mode, and background color.

For starters, just set the resolution at 72 pixels per inch. If it’s not set at 72 pixels per inch, click on the text field beside ‘Resolution’, delete the existing value, and key in “72”). If you don’t know anything about resolution and want to know what it is and what it is about, I have a little tutorial on it here.

For the height and width, I’ll leave them up to you. Just don’t make it so darn big or ridiculously small. By the way, Photoshop allows you to choose from several units of measurement with which to define your canvas’ dimensions (pixels, inches, centimeters, millimeters, points, picas, and columns). To select a unit of measurement, simply click on the button at the end of the dropdown menu field labeled “Height” (or “Width”) and click on the unit of measurement of your choice. (Note: Changing the unit of measurement of the height will also change the unit of measurement of the width and vice-versa)

If you’re not very good with measurements, you may want to just choose from the preset canvas sizes provided. To do so, simply click on the button at the end of the dropdown menu field labeled “Preset” and click on the canvas size of your choice.

We’ll leave the background color set to “White” for now. If it’s not set to “white”, click on the button at the end of the dropdown menu field labeled “Background Contents” and click on ‘White’.

As for the ‘Color Mode’, just make sure it’s set to ‘RGB’ and ‘8 bit’. If it’s not set to ‘RGB’ and ‘8 bit’, I suppose you already know what to do.

Just ignore anything else that you might see on the “New” window/dialog box.

Now, click on the ‘Ok’ button and Voila! You now have your very own blank canvas.

Saving Your Work

Just like in any other programs, saving your work in Photoshop is very easy. Simply click on ‘File’ and then ‘Save’. That’s it... well, not really. Since Photoshop supports a big bunch of file formats, it provides you with as much formats with which to save your work. Choosing the file format with which to save your work depends on a wide variety of factors which includes number of colors, image quality, presence of additional/custom channels, and presence of “layers”, among others. But talking about this will provide enough material for another article. I’ll probably make a discussion on this next.

Anyway, (again, unless you already know something about the different file formats) to make sure that you’ll be saving your work with everything that you will be doing or have done (consciously or otherwise) intact, it would be best that you just go with whatever format Photoshop recommends you to save your file in.

If you are clueless about this, it would be best for you to just leave the “Format” as it is (the format you see on this screenshot may not be the same as what you might see on your screen, it’s ok, don’t panic).

Depending on what you have in your work (please refer to above mentioned factors), if you choose a format which is not compatible with your work, you may see messages warning you about stuff.

Experiment!

Now that you already know how to “produce” a canvas and save your work, I’ll leave you on your own for now. Just play around with the various tools that you see on screen. DO NOT BE AFRAID. Photoshop won’t bite you.

The above illustration (not to scale) shows a 9 pixel-per-inch horizontal line (a) and a 9 pixel-per-inch vertical line (b). Go ahead, count the squares that you see. It also clarifies what I meant by a “one-pixel-thick line”.

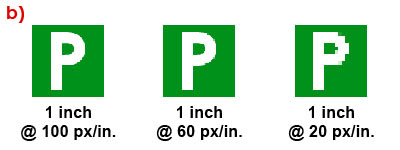

So, why “pixels-per-inch”? Why not say the image is this much pixels tall and that much pixels wide? Well, if you do the latter, you’re actually stating the dimensions of an image and not the resolution. Always remember that resolution and dimension is not in any way the same. They are not even similar to say the least. Take a look at the following examples: